Understanding Arizona Bankruptcy Laws and Procedures

Learn how Arizona bankruptcy laws work, including exemptions,chapters, court locations, and practical next steps.

Arizona Bankruptcy Laws: What to Know Before You File

If you’re searching Arizona bankruptcy laws, you may be dealing with collection calls, past-due payments, a lawsuit threat, or concern about wage garnishment, foreclosure, or vehicle repossession. This page explains what bankruptcy in Arizona typically looks like, where federal rules apply, and where Arizona-specific rules matter most—especially Arizona bankruptcy exemptions (the laws that may protect certain property).

This is general educational information, not legal advice. Results can depend on income, household size, assets, recent payments or transfers, prior filings, and how federal and local rules apply in the U.S. Bankruptcy Court for the District of Arizona. If you’re facing a deadline—like a scheduled trustee sale, a court hearing, or an active garnishment—getting individualized guidance quickly can help you avoid expensive mistakes.

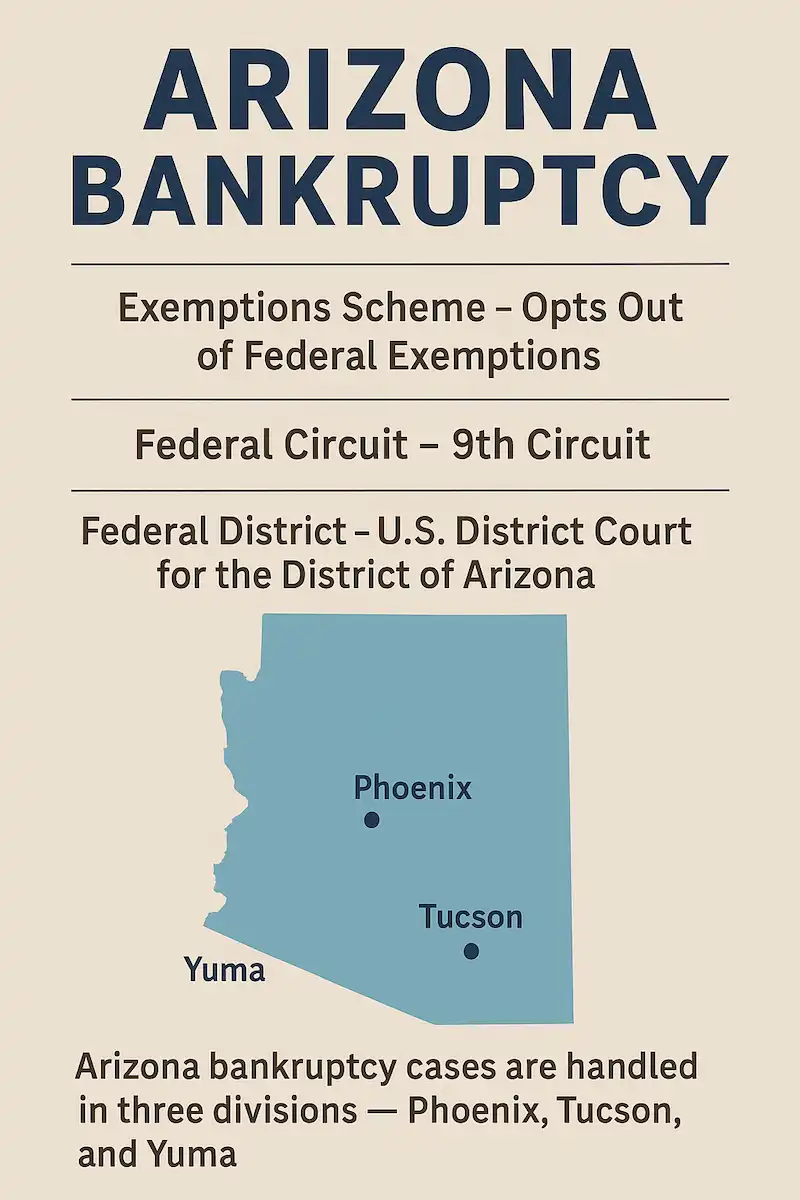

Bankruptcy in Arizona — At a Glance

- Federal case, Arizona details: Bankruptcy in Arizona is a federal court process under the U.S. Bankruptcy Code. Arizona law still matters—especially for Arizona bankruptcy exemptions and certain District of Arizona procedures.

- Most consumer cases: Individuals most often file under chapter 7 (many cases move faster and can discharge qualifying debts) or chapter 13 (a structured repayment plan, often 3–5 years, with a discharge after successful completion).

- Chapter 7 and the means test: Qualifying for chapter 7 in Arizona often involves the means test, which begins with average household income over the last six months compared to the Arizona median. If income is above median, the analysis then considers allowed expenses and other factors. Being above median does not automatically mean you can’t file chapter 7.

- Arizona is an opt-out state: Arizona generally requires most filers to use Arizona bankruptcy exemptions rather than the federal exemption set. A federal residency “look-back” rule can affect which state’s exemptions apply if you moved recently.

- Timeline (typical): Many straightforward chapter 7 case in Arizona filings reach discharge in roughly 3–4 months from filing. Chapter 13 usually runs 3–5 years because it’s built around plan payments.

- Automatic stay: Filing usually triggers the automatic stay, which can stop or pause many collection actions (lawsuits, garnishments, repossessions, and certain foreclosure activity) while the case is pending. Some actions are not stopped, and repeat filings can limit the stay.

- Trustee + 341 meeting: Every case is assigned a trustee and includes a 341 meeting of creditors. Many meetings in Arizona are held remotely and are brief when paperwork is complete, but the format and timing are controlled by your official notice.

Understanding Bankruptcy in Arizona: What It Can (and Can’t) Do

Financial stress often starts with something ordinary: job loss, medical bills, divorce, rising housing costs, or a business slowdown. Bankruptcy is designed to create an organized process for dealing with debt. Depending on your chapter and your facts, it may:

- pause many collection efforts through the automatic stay (with important exceptions),

- discharge many qualifying unsecured debts, and

- provide a structured plan in chapter 13 to catch up on certain arrears.

Bankruptcy generally does not wipe out every debt. For example, child support obligations are not dischargeable. And bankruptcy is paperwork-heavy—accuracy and completeness matter. The best outcomes usually come from filing the right chapter at the right time and using the correct exemption strategy for your assets.

The Purpose of Bankruptcy

Bankruptcy law tries to balance two goals: (1) giving an honest debtor a realistic chance at a fresh start, and (2) treating creditors consistently under the rules.

In chapter 7, a trustee reviews your paperwork, including Arizona bankruptcy exemptions, and may administer non-exempt property. Many consumer cases are “no-asset” cases where nothing is sold. In chapter 13, you propose a court-approved plan, make payments over time, and—if you successfully complete the plan—receive a discharge of eligible remaining balances.

What Happens When You File Bankruptcy in Arizona?

Filing a bankruptcy petition starts a federal case in the U.S. Bankruptcy Court for the District of Arizona. While each case is a little different, most follow a predictable sequence:

- You file the petition and required schedules and statements.

- The automatic stay usually begins and can pause many collection actions.

- A trustee is assigned and you attend a 341 meeting of creditors.

- In chapter 7, the trustee reviews exemptions, income documents, and asset issues; in chapter 13, your plan is reviewed for confirmation.

- If requirements are met (including required courses), the case moves toward discharge (chapter 7) or plan completion and discharge (chapter 13).

Two “Before You File” Tips That Prevent Common Problems

- Collect documents early: pay stubs, tax returns, bank statements, and vehicle/home loan statements are common trustee requests.

- Avoid big money moves: repaying a family member, selling a vehicle, or transferring property can create avoidable issues—even when your intentions are good.

Types of Bankruptcy

Most consumer filings in Arizona are chapter 7 and chapter 13. Chapter 11 is more common for businesses, but some individuals with higher debt levels or complex finances may use it.

Chapter 7 Bankruptcy in AZ

Chapter 7 bankruptcy in AZ is often used to discharge qualifying unsecured debts like many credit cards, medical bills, and personal loans. In many consumer cases, filers keep their property because exemptions cover what they own and there is no non-exempt property for the trustee to administer. When there is non-exempt property, the trustee’s role is to review it under the rules and, if appropriate, administer it for the benefit of creditors.

Eligibility often depends on the means test. You can also learn more about chapter 7 here.

Eligibility for Chapter 7

The means test considers household income and allowed expenses to help determine whether a filer belongs in chapter 7 or in a repayment chapter like chapter 13. Importantly, being over the median does not automatically prevent a chapter 7 in Arizona filing. Outcomes can depend on household size, the type and stability of income, secured debt payments, allowed expense deductions, and other factors.

For a deeper explanation, see our means test guide.

Comprehensive Arizona Bankruptcy Guidance & Resources

Expert insights and clear information to guide you through bankruptcy in Arizona, from Phoenix and Tucson to every community statewide.

Chapter 13 Bankruptcy in AZ

Chapter 13 bankruptcy in AZ involves a court-approved repayment plan that typically lasts 3 to 5 years. It can be a useful tool if you’re behind on a mortgage or car loan and need time to catch up, if you have income that supports monthly payments, or if chapter 7 is not a good fit due to the means test or non-exempt equity.

Chapter 13 has more moving parts than chapter 7. Some secured and priority debts may be paid through the plan. How interest and claim treatment work can vary depending on the type of claim and what the Bankruptcy Code allows. Learn more about chapter 13 here..

Arizona Bankruptcy Laws Overview

The Bankruptcy Code is federal, but Arizona law and District of Arizona procedures can affect real outcomes—especially what property you can protect and what trustees request.

Federal vs. State Bankruptcy Laws

Federal law controls the core structure: which chapters exist, how discharge works, the means test framework, and many deadlines. State law matters heavily for exemptions. That’s why two people with similar debts can have different “keep vs. risk” outcomes in different states.

Arizona Bankruptcy Exemptions

Arizona bankruptcy exemptions can protect certain property such as home equity, vehicles, household goods, tools of the trade, and many retirement accounts (rules and limits apply). Arizona is an “opt-out” state, which generally means most Arizona filers use Arizona’s exemption system rather than the federal exemptions.

A federal residency look-back rule can affect which state’s exemptions you must use if you moved recently. People often summarize this as “you must be in Arizona for 730 days,” but the real analysis can be more nuanced depending on where you lived before Arizona and when you moved. For a deeper overview, see Arizona's bankruptcy exemptions here..

Arizona also has a well-known homestead exemption that may protect equity in a primary residence, but how it applies can depend on facts like title, occupancy, equity, liens, timing, and whether a property is actually your primary residence. If your home is your main asset—or if you’re behind on payments—it’s especially important to review chapter choice and exemption planning before filing. Learn more about the Arizona homestead exemption here..

Arizona-Specific Procedures

Bankruptcy forms are federal, but the District of Arizona has local rules, local forms, and local practices that can affect filing requirements, hearing procedures, and trustee document requests. Your case notices (and your docket) are the official source for the deadlines and instructions that apply to your specific case.

If you want a neutral reference point, the court’s website posts current local rules and basic filing information. U.S. Bankruptcy Court for the District of Arizona (official site).

Why Accuracy Matters

Bankruptcy paperwork is detailed. Missing documents or inconsistent information can lead to delays, dismissal, or disputes that cost time and money. Another common pitfall is accidentally exposing an asset that could have been protected with the correct exemption approach. A qualified Arizona bankruptcy attorney can help you choose the right chapter and apply Arizona bankruptcy exemptions correctly.

How Do I File for Bankruptcy in Arizona?

Most Arizona filings follow the steps below. The exact documents and deadlines can vary by chapter, your circumstances, and local requirements.

1) Credit Counseling

Before you file, you must complete a credit counseling course from an approved provider (with limited exceptions). The course is a legal prerequisite in most cases and must be completed within the required time window.

2) Prepare and File the Petition

You file a petition and a set of schedules and statements that list your assets, debts, income, expenses, recent transfers, and other information. Accuracy matters. Even honest mistakes can trigger trustee follow-up requests, amendments, delays, or—in some situations—bigger problems if information is omitted.

Practical Document Checklist (Common Starting Point)

Exact requests vary by trustee and by case. These are common items many people gather to reduce last-minute stress:

- Recent pay stubs or income proof (including benefits)

- Recent bank statements

- Most recent tax returns

- Vehicle and mortgage statements (if applicable)

- Debt list (credit cards, medical bills, loans, collections, lawsuits)

- Information on recent transfers, large payments, or sales

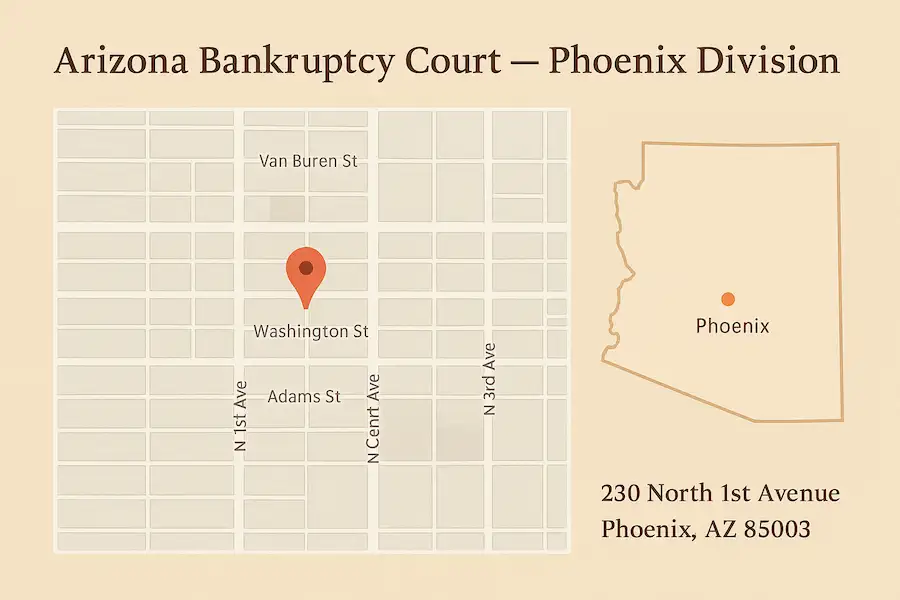

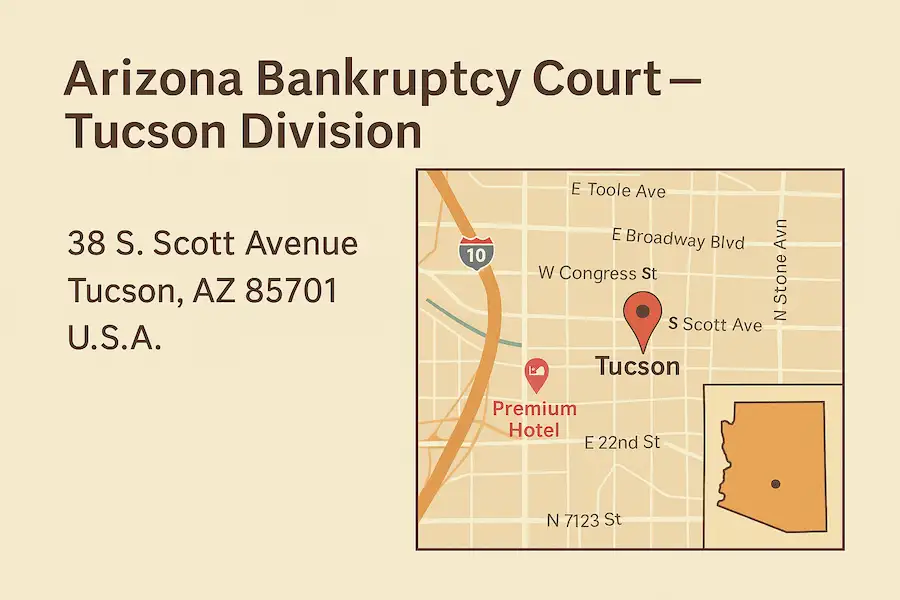

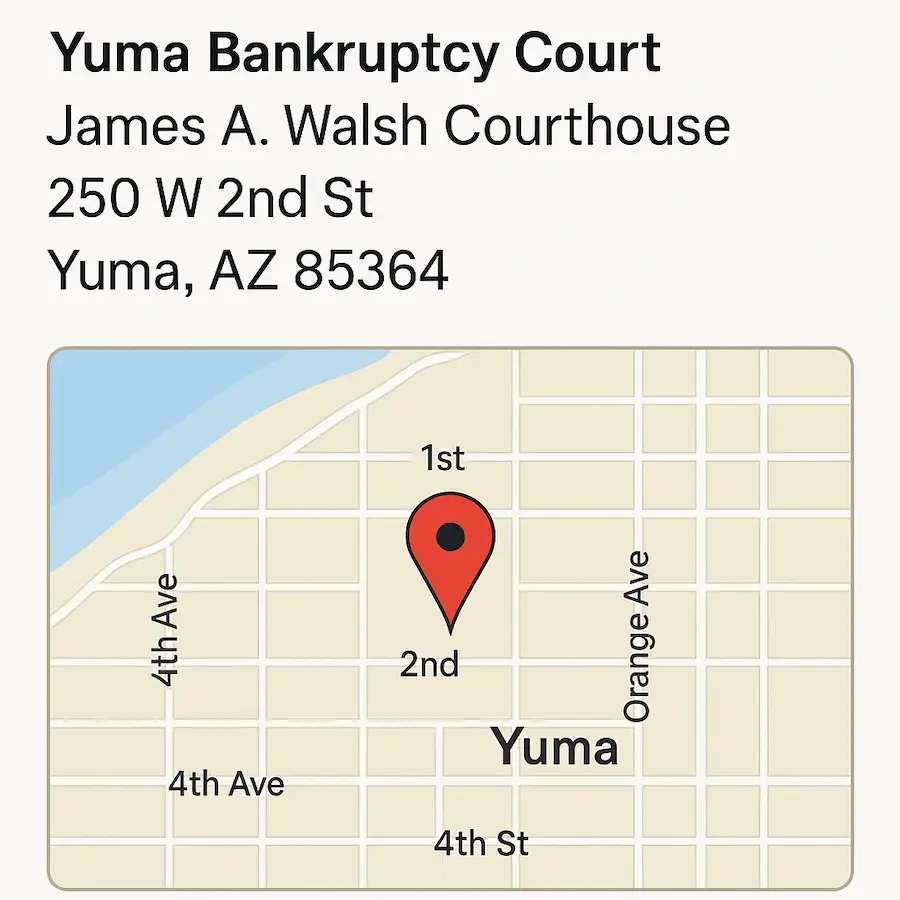

Which Arizona Bankruptcy Court Handles Your Case

The U.S. Bankruptcy Court for the District of Arizona administers cases statewide. Where you live can affect division assignments and how certain matters are calendared. Because procedures can change, always follow your official notice for the 341 meeting of creditors and any hearings. Many 341 meetings of creditors in Arizona are conducted remotely, and your notice provides the official instructions.

The court maintains offices in Phoenix and Tucson, and some matters may involve other locations depending on the case and calendar. If you see an address on an infographic or older resource, treat it as a helpful starting point—not a substitute for your current notice and the court’s website.

3) Filing Fees and Costs

Costs commonly include the court filing fee, the required courses (credit counseling and debtor education), and attorney fees (if you hire counsel). Fees and course pricing can change over time. Some people may qualify to pay the filing fee in installments, and some chapter 7 filers may request a fee waiver if they meet strict criteria.

4) The Automatic Stay

The automatic stay usually begins when you file. It can stop or pause many collection actions—like most lawsuits, wage garnishments, repossessions, and certain foreclosure steps—but it does not stop everything. For example, many family court matters and child support enforcement actions can continue, and some tax-related or criminal matters may be outside the stay. Creditors can also ask the court for permission to proceed (“relief from stay”) in certain circumstances. If you’ve filed bankruptcy recently, the stay can be limited or may not go into effect without court action.

5) 341 Meeting

The 341 meeting of creditors is where the trustee asks questions under oath about your finances and paperwork. Creditors can appear, but many do not in routine consumer cases. Being organized and responsive to trustee document requests is one of the best ways to keep a case moving smoothly.

6) Debt Discharge

In chapter 7, discharge is often entered a few months after filing if the case is straightforward, required courses are completed, and there are no objections. In chapter 13, discharge comes after you complete your plan and meet all plan and course requirements. Some cases take longer than the “typical” timeline due to trustee requests, asset issues, amendments, or litigation.

Types of Debts Discharged

Bankruptcy can discharge many unsecured debts, but not all. Debts that often survive include child support, alimony, many recent taxes, and most student loans (unless you meet a separate legal standard in an adversary proceeding). Some debts can also be challenged as non-dischargeable based on fraud or similar allegations, depending on the facts and whether a timely lawsuit is filed in the bankruptcy case.

Frequently Asked Questions About Bankruptcy in Arizona

How Much Does It Cost to File Bankruptcy in Arizona?

Costs commonly include the court filing fee, required courses (credit counseling and debtor education), and attorney fees (if you hire a lawyer). The most reliable numbers are the current court fee schedule and course provider pricing at the time you file. Some filers can request installments, and some chapter 7 filers may request a fee waiver if they meet strict requirements.

How Do You File for Bankruptcy in Arizona?

Filing bankruptcy in Arizona generally means: gathering financial documents (income, expenses, debts, assets), completing an approved credit counseling course, preparing the petition and schedules, filing in the U.S. Bankruptcy Court for the District of Arizona, and then attending the 341 meeting of creditors. After that, the case proceeds toward discharge in chapter 7 or plan confirmation and completion in chapter 13.

Can Inherited Property Be Included in a Bankruptcy in Arizona?

Yes. Inheritance can become part of the bankruptcy estate depending on timing and the chapter. If you become entitled to an inheritance before filing, it is typically part of the case. If you become entitled to an inheritance within 180 days after filing, it may also be included under bankruptcy law. Whether it is protected depends on the facts and whether an exemption applies. This is very fact-specific, so it’s wise to get legal advice before you accept, spend, transfer, or disclaim an inheritance if bankruptcy is on the table.

You can also review our Arizona chapter 7 guide for a deeper overview of how chapter 7 works.

Can I File Bankruptcy Without My Spouse in Arizona?

Yes. You can file an individual bankruptcy in Arizona even if you are married. Because Arizona is a community-property state, the filing can still involve community income, community debts, and community assets, and a spouse’s income is often relevant to the means test and household budget calculations. Whether one spouse should file or both spouses should file depends on the debts, assets, income, and goals.

For a deeper dive, see Can Just One Spouse File Bankruptcy?.

How Long Does Bankruptcy Take in Arizona?

A typical consumer chapter 7 case often runs about 3–4 months from filing to discharge when paperwork is complete and there are no disputes. A chapter 13 case lasts longer because it is built around a 3–5 year repayment plan.

To compare the two paths, see our Arizona chapter 7 page and Arizona chapter 13 page.

How Much Does a Bankruptcy Lawyer Cost in Arizona?

Attorney fees vary by chapter, complexity, and local practice. Many attorneys charge a flat fee for a routine chapter 7 case, while chapter 13 often involves different fee structures and may be paid in part through the plan (subject to court rules and disclosure). The most accurate quote usually comes after a lawyer reviews your income, assets, debts, and goals.

How Often Can You File Bankruptcy in Arizona?

You can file bankruptcy more than once, but there are waiting-period rules that control when you can receive a discharge again. For example, after a prior chapter 7 discharge, there is generally an eight-year waiting period (measured from filing date to filing date) before you can receive another chapter 7 discharge. Other chapter combinations have different waiting periods and exceptions.

For more detail, see How Often Can You File Bankruptcy?.

Final Thoughts: Making a Clear Plan Under Arizona Bankruptcy Laws

Understanding Arizona bankruptcy laws can help you make calmer, more informed choices—especially when you’re deciding between chapter 7 and chapter 13, and when you’re trying to protect property using Arizona bankruptcy exemptions. If you’re under pressure from deadlines or active collection activity, individualized guidance can be especially important.

Urgent Financial Issues

If you are facing foreclosure, vehicle repossession, or wage garnishment, timing can matter. Filing a bankruptcy case can trigger the automatic stay, but it often needs to happen before certain events (like a foreclosure sale) to be effective. The safest approach is to get advice quickly if you have a known court date, sale date, or repossession risk.

Collection lawsuits can also lead to judgments, liens, or wage garnishments. Bankruptcy can stop many lawsuit and judgment-enforcement actions, and may discharge the underlying debts depending on the chapter and the type of debt.

Urgent Bankruptcy Help for Arizona Residents

Take immediate action to protect your home, vehicle, and income from foreclosure, repossession, and wage garnishment. Solutions tailored specifically for Arizona residents.

Explore Our Arizona Bankruptcy Guides

Explore Bankruptcy Help by State

Browse our state guides to learn exemptions, means test rules, costs, and local procedures. Use these links to jump between states and compare your options.

- Arizona

- California

- Colorado

- Florida

- Georgia

- Illinois

- Indiana

- Maryland

- Michigan

- New York

- Ohio

- Oregon

- Pennsylvania

- Tennessee

- Texas

- Virginia

- Wisconsin